When telling a story set in a fantastical, science fictional, or speculative world, you don’t necessarily need a high concept to make it work—but it never hurts. There’s a reason why John Scalzi hosts a series of essays by other writers called “Big Idea” and why Kieron Gillen’s concepts of “First It” and “Second It” are one of the most memorable bits of storytelling advice I’ve encountered in recent memory.

But there’s a downside to big ideas as well: Have too many of them in a single work and you risk distracting from the other things that make for a great story, including memorable characters, surprising interactions, and a solid sense of place. Earlier this year I wrote about a novel that—for me, anyway—had this very flaw: It did a little too much for me to ever be as fully engaged in the narrative as I’d wanted to be.

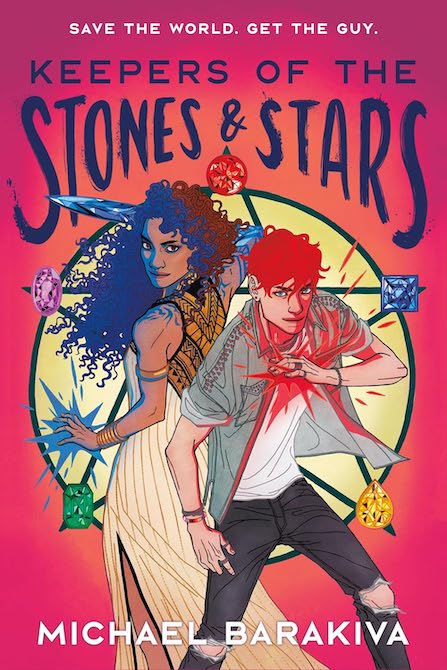

As I made my way through the first half of Michael Barakiva’s novel Keepers of the Stones and Stars, I was worried I might encounter the same issue here. It begins with a fairly traditional setup: Protagonist Reed is a high school student who’s just kissed his crush, Arno, for the first time when he’s pulled into a much grander cosmic conflict. In this case, the pulling is done by Mr. Shaw, a college consultant at Reed and Arno’s high school who has an impressive command of languages, a penchant for pop-culture references, and an impeccable sense of style.

We’ll eventually discover that his first name is Rupert, and if you think a high school student learning of their world-changing destiny by an older mentor named Rupert is a little familiar, don’t worry; both Reed and Shaw are well-versed in their pop culture tropes. One chapter is titled “Reed Smells an Info Dump,” and there are nods to the DC Universe and “The Series That Shall Not Be Named,” among many others. And at one point, Shaw tells Reed that he’s “succumbing to the same old-fashioned, heteronormative, patriarchal idea of heroism.”

Buy the Book

Keepers of the Stones and Stars

Reed learns that he is now the Bearer of one of a group of magically-endowed stones that are used to close something called the Pentacle Portal, and that a new group of bearers is selected every 37 years when a comet comes close to Earth. “[T]he Ikeda awakens both the possibility of apocalypse and the tools by which to remedy it,” Reed observes at one point.

Reed’s stone is red, and Shaw informs him that each stone’s Bearer will be led to the next one in turn. And soon enough, they locate Alejandra, a skilled fencer in possession of the blue stone. Each gives its Bearer different powers; in Reed’s case, that involves empathy—and some of this novel’s more interesting touches come when Barakiva explores the range of uses of such abilities and the ethical quandaries they can put Reed in. Reed is a musician as well, and he views his abilities through a musical lens, visualizing chord progressions to get himself through difficult tasks.

The addition of Alejandra into the mix includes a few chapters written from her perspective, and that puts some of the other characters in a new light. While Shaw is prone to making comments like, “Nothing like a Magicians season five reference,” Alejandra has less time for such things. “Again, I nodded as if I understood their obscure allusions,” she notes at one point.

This gathering of the party isn’t without its conflicts, including one with a powerful figure known initially as JoAnne who wields illusion-casting powers and has a serious grudge against Shaw. Reed, Alejandra, and Shaw eventually link up with the next chosen Bearer, a fencing rival of Alejandra’s named Hikaru who winds up with the yellow stone.

If you think that’s a little problematic, you’re not alone. “It’s like Power Rangers-level racism,” Hikaru say, and while it’s good that the book is self-aware about this, it’s less clear why the framework of the novel was such that Hikaru ended up with this particular stone. There’s a bit of real-world history here, in that the 17th-century poet and scientist Zeb-un-Nissa plays a significant role in the book’s backstory. But while this is a book that’s eminently aware of race, class, gender, sexuality, and power dynamics—and has a cast of characters to match — Hikaru’s frustrations still stand out somewhat.

[Spoilers follow.]

Halfway through the novel, Barakiva delivers a rug-pulling moment, revealing that there are plenty of things that Shaw and his father—referred to only as “Father,” which is rarely a good sign—haven’t told the Bearers. This forces Reed to rethink everything he’s been told so far and sends him in a very different direction in the novel’s second half, even as interspersed communications between the Shaws offer a sense of what they’re up to.

Throughout the novel, there’s both an uptick in betrayal and a sense of nearly all of the characters reinventing themselves in some way. Nearly everyone faces fundamental questions about themselves—whether it’s their place in the world, their identity, or their connection to other people. And Barakiva also weaves in a few tantalizing glimpses of what took place with previous Bearers and of the dissonance between the magical energies at the heart of this novel and contemporary technology. It ends up situating this narrative somewhere between Elizabeth Knox’s The Absolute Book and Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie’s The Wicked & The Divine.

Keepers of the Stones and Stars is a compelling read, and the big narrative shifts that occur throughout it end up feeling earned rather than arbitrary. It doesn’t hurt that this novel’s sense of place feels grounded. Much of the novel is set in Reed and Arno’s hometown of Asbury Park, New Jersey. I grew up just north of there and found the version of the city thoroughly recognizable, including a sequence where our heroes spend some time at The Empress, a hotel that’s been present there for decades. In addition to his forays into fiction, Barakiva is also a theater director, and one supporting character’s experience in that world also feels lived-in, with a few unlikely moments of humor, including mention of a “site-specific The Three Sisters” that sounds less than enticing.

In fact, some of the more quotidian details here make for the novel’s best moments. When Arno re-enters the plot, Barakiva reveals plenty about him, and his musings on his Armenian heritage and his interest in embracing both his religious faith and his sexuality—and his refusal to see them as being in conflict, despite what his conservative family believes—makes him the book’s most interesting character.

That doesn’t mean that there aren’t plenty of expansive moments of worldbuilding present here as well, though. Between glimpses of earlier Bearers and a framing device that hints at what takes place after this novel’s conclusion, Barakiva has created a welcome blend of the familiar and the fantastical. And in a book about balance, its own inner gauges are largely running in harmony.

Keepers of the Stones and Stars is published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux Books for Young Readers.